When I bought my Subaru STI a few years ago, I had big plans for it. I would drive it in track events and I would modify it for asphalt-kicking horsepower (insert grunting noises here). Unfortunately, Reality had other plans for my car.

My track event was a minor engine disaster. And my costliest modification so far is rubber floor mats. (I’m not counting trivial replacement parts, like new engines.) Apparently one of the rules of fatherhood is feeding your children, and if there’s any money left over after groceries, roofs, and decorative bathroom fixtures, then you can buy a bigger turbo. I mention this as a reminder to always read the fine print.

There is a small, bright spot, however. My car came with a game. On the dash is a little display for the average gas mileage with respect to the trip odometer. The game is to make this number as high as possible.

Numbers never lie. Except this time.

One would think that a number presented to you by your car would be accurate, just like information from the internet. But like most traffic laws in Michigan, this turns out to be just a mere suggestion. The number tends to read a little high in my daily commute, and a bit low on extended freeway driving when compared to my calculations based on actual gas bought and miles driven.

But that’s not the point. It doesn’t have to be accurate, it just has to be LARGE. America, #$%!, yeah! Or so the song goes.

“If you cannot do great things, do small things in a great way.”

—Napoleon Hill

I’ve talked about hypermiling before. Hypermilers try to maximize their fuel efficiency. In theory, I could use their techniques to increase my gas mileage, but they’re weird and I don’t want to be associated with them.

Besides, I only have two techniques for making the gas mileage number as high as possible that are totally not like those hybrid-owning, anti-recycled dinosaur fuel, hypermiling drivers—coasting and light acceleration.

Coasting

This is probably the easiest and most common technique. On my daily commute, I have a few stop signs that are at the bottom of a slope, and a couple of big hills I drive down. For these areas, I use a “lift throttle” point. On a race track, there are certain braking or turn in points that drivers use when going around corners. My lift throttle points are similar.

At a certain speed I lift off the throttle at a specific point and coast to the stop sign, trying to maximize both speed and coasting distance. I adjust to conditions, like traffic and weather.

On bigger hills, other cars better get out of my way. I don’t care how fast I’m going—I’m not touching the brakes until I’m bumper distance to the car ahead of me.

I coast for a traffic light that I can’t catch or for stopped traffic. Basically, my mindset is that braking is bad.

I also try carrying as much of my speed as I can through freeway exit ramps, not necessarily for gas mileage reason, but okay—we’ll use that reason for the sake of discussion. Be sure to avoid the guard rails as the friction from sliding along them really hurts your gas mileage. Just a pro tip.

I have one additional note about coasting. In most cars, if you lift off the throttle, the engine goes into deceleration fuel cut-off (DFCO). In this mode, the injectors shut off, cutting fuel to the cylinders, increasing engine drag. This happens when the car is in gear. If you shift to neutral while coasting, however, your car is simply rolling while idling, and is not the same as DFCO.

Having explained that, when I log engine data from the car on my laptop, the instantaneous gas mileage while coasting is slightly higher when in neutral (150+ mpg) than when in gear (125+ mpg). That is the opposite of what I just explained and what I expect. I’m guessing their algorithm for instantaneous gas mileage is wrong or there’s some effect that’s not being considered. Or I have no idea what I’m talking about, which tends to happen a lot on this blog for some reason.

In any case, I will sometimes coast in neutral to boost my numbers even though this isn’t really what’s happening (I think). My game is making the gas mileage indicator high, not getting high gas mileage, right?

Light Acceleration

Light acceleration is really just to prevent the gas mileage number from dropping too much, not for increasing it. Because like gas prices in reverse, the gas mileage tends to go down quickly, but take forever to go back up.

Every time I accelerate slowly from a stop, I am going against every fiber, sinew, bone marrow, neuron, Americanized red blood cell of my being. My brain wants to explode each time I feather the gas pedal, but luckily my abnormally thick skull keeps all the gooey mess together.

And hey, I get better gas mileage numbers, which is what this game is about.

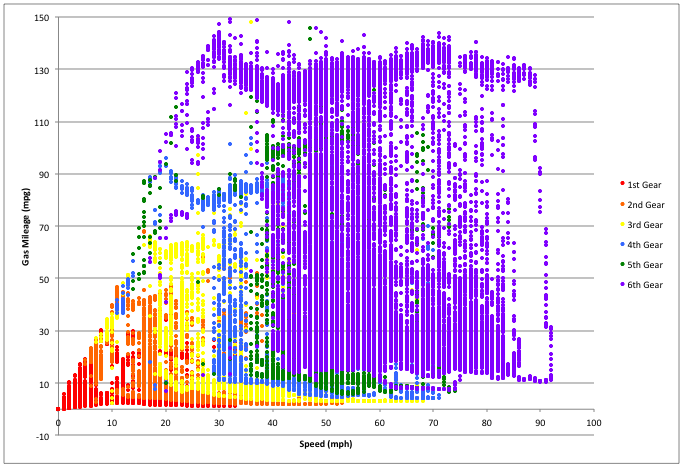

I put together this Excel graph of my drive to and from work, over 90 miles in total. (In all honesty, this is just another expression of my love of Excel.)

Since I drive a manual transmission car, I broke it down by gear (1st-6th). On the x-axis is speed, and the y-axis is miles per gallon. The gears are in color. I should have included throttle position, but that’s why I make a bad test engineer.

If you squint just right, you can just make out Ansel Adam’s Moon and Half Dome in Technicolor®

What did I learn, other than how to make rainbows like my kids? It is not possible to get good gas mileage in 1st gear. The largest variation is in 6th gear. If I’m accelerating hard, I get bad gas mileage. If I coast, I get fantastic mileage. I should coast in the highest gear as much as I can. Rocket scientists don’t have to worry about their job security.

My Results

After 148,519 miles, the average gas mileage based on this display is 24.0 mpg. The real gas mileage, however, is only 23.0 mpg, based on actual calculations. For a mileage to count, I have to go at least 200 miles. That’s an arbitrary number for my arbitrary game. So the mpg display in the car is on average 1 mpg off on the high side.

The best indicated gas mileage I’ve recorded is 32.4 mpg after 259 miles during my drive to Key West. This was done at 80°F, with winter tires, the air conditioning on for half the distance, and driving 50-60 mph most of the way.

My worst was 12.3 mpg, after the track event that I’m still trying to forget about.

“You need to let the little things that would ordinarily bore you suddenly thrill you.”

—Andy Warhol

Random Factors

I’ve found the following factors possibly affecting my gas mileage numbers. I haven’t confirmed them all, so these are presented anecdotally.

Temperature

I get better gas mileage in warmer weather than colder weather. According to the U.S. Department of Energy:

…in short-trip city driving, a conventional gasoline car’s gas mileage is about 12% lower at 20°F than it would be at 77°F.

On my Key West trip, I went from an indicated 18.3 mpg in the frigid, sub-zero Upper Peninsula of Michigan to 23.1 mpg in balmy, 80°F, only one peninsula Florida.

My guesses for the difference are longer warm-up times and air/fuel ratios for colder temperatures.

I’ve found a number of factors that are indirectly related to this besides temperature, such as winter/summer tires (see below) and winter/summer gas.

There are different standards for gas in winter and summer. The result is that winter gas tends to have more butane than summer. This makes winter gas cheaper, but it also has less energy content than summer gas, leading to worse gas mileage.

(From what I read on the interwebs, in Michigan, we would typically get summer gas from Memorial Day to Labor Day.)

Tires

One tire theory is that in winter, tires tend to have less air pressure due to temperature, reducing gas mileage.

I get a different effect with my winter tires, however. My winter tires have lower rolling resistance than my summer tires, and they are slightly smaller (235/45-17) than my summer tires (245/40-18). So that means I can coast more in winter tires, and my odometer will indicate that I drive a little more than 1% further than summer tires, giving me slightly higher indicated gas mileage.

Air Conditioning

I did the experiment in my hypermiling post. Driving with the windows closed and no air conditioning is best for gas mileage, obviously. I’ve also tried at various times an experiment with the windows down vs. air conditioning. In my Honda it was the middle ground, and in other attempts, it was inconclusive.

Generally the reason I drive without air conditioning is for horsepower. In my 944, turning on the air conditioner felt like losing half of my horsepower. My Honda is powered by hyperactive squirrels that hate me because they slow down when I turn on the air conditioning.

In today’s new cars, I think the difference between air conditioning on or off is negligible. My advice for most people is to save money on antiperspirant and just turn it on.

Drafting

Mythbusters has already confirmed that this works. I just can’t do it, game or no game. It goes against EMan’s Road Rule #1—pass early, pass often.

Country Roads

I’ve been altering my route to-and-from work for years now. I’ve settled on a route that lets country roads take me home. It’s longer, but I have less traffic, fewer traffic signals, and less stress. I tend to drive around 50-60 mph on these roads. Better gas mileage is just a bonus.

Big Hills

I like big hills and I cannot lie. You other drivers can’t deny, that when a car drives up on an itty bitty road with a roundabout in your face, you get sprung …

Oh, sorry. I was just thinking about the roundabout and hill on Kensington Road.

A Cry for Help

Basically, this is a passive-aggressive person’s obsession for a bigger turbo. I may actually have turbo envy. What I’m saying is I need a call-in show, like Dr. Jay Leno’s Garage. Or an advice column written by a car guy.

Crankiness Rating: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(Gas mileage? Are we really talking about gas mileage?!)

![]()